(or “what I learned when the tests I have done to others, were done to me”)

The tests presented in this post are intentionally not explained thoroughly here. I have focussed, currently, on patient experience. If you wish to learn more about the things presented here, and the interpretation of the possible results, wait for them to be explained in your lectures, or, perform a quick Google search.

Before the new semester began proper, I was asked to assist with some physiology practicals on my campus. I agreed because I felt (much in the same way a chef will sample his/her food before selling it to the masses) that it would be good for my overall learning to experience the same anxieties and physical exertions -if applicable- that a patient may endure when they undergo physiological testing. When one repeatedly performs tests day in, day out, it’s easy to forget that the patient likely does not have anywhere near the same levels of familiarity with the procedure and proficiency with them as that of you, the practitioner, so to gain an insight into the emotional and physical aspects from the other side would, I felt, be good practice.

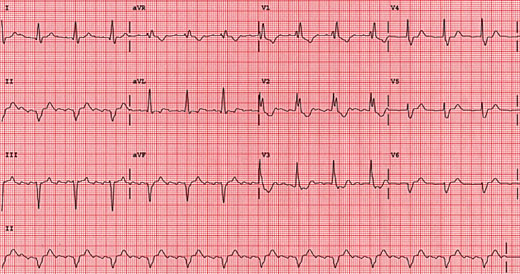

Day one was one of a cardio nature, in that I performed lots of exercise tests at a physiologist’s disposal. (Some of these tests are reserved for respiratory physiologists, but if you’re studying and are not yet at the point of choosing which PTP pathway to follow, you’ll experience these, too).

I discovered upon entry, that I would be performing the following:

- YMCA step test

- Bleep test

- Treadmill test: ramp protocol (similar to the Bruce Protocol)

The wait to enter the lab was, (obviously not the same in terms of anxiety levels, but regardless) akin to a patient’s wait to enter a clinic testing room; knowing that I was going to have to perform tests, but not knowing exactly what they were was rather nerve-jangling (especially considering my then-unknown weight gain after the obligatory food-filled, sedentary lifestyle commonly experienced over the festive break).

The real difficulties stemmed from trying to comprehend the techniques required for each test. Explaining, or writing about them is one thing, but actually doing them is another thing entirely.

The YMCA step test itself wasn’t particularly challenging, given that it only involved 3 minutes of steady box steps. The difficulty came in not influencing heart rate on recovery. Knowing that my HR was being documented every minute meant I kept looking at the oximeter, and as has been documented (a quick google search will give you confirmation of this), it is relatively easy to change your HR on command.

For a patient, this last point may not be of particular issue, given that they might not be particularly aware of the potential influence they can have on their HR, but I can easily see how repeatedly stepping onto and off of a box could be difficult task for a patient of advanced age.

Bonus Clinical Perspective: In this test the Heart Rate Recovery and VO2 max doesn’t appear to be particularly accurate, when using normal values, especially when compared with the VO2 max displayed through the other tests, either. The values are based on age, as oppose to individual physiological characteristics, so assume a physical ideal that doesn’t necessarily transcend to real life.

The bleep test wasn’t like ones I have previously attempted in the gym, or what have you; rather, it was more about timing, ensuring there were no stops. This involved slowing down so as to reach the end of the designated track in time with the beep, then speeding up to repeat, meaning that pacing yourself was a must. The resulting strain on my legs caused them to become incredibly painful, incredibly quickly..! (I’m aware that bleep test procedure differs between fitness centres, so forgive my whinging if you use this format regularly).

Encouraging a patient to exhaust themselves doing this test would take a great deal of commitment from both parties; I’m not particularly unfit, but I had nothing tangible to aim for, with regards to an end point, so with no time to “beat”, I didn’t have anything to work towards and as a result, I gave up after 10 or so minutes, despite the fact I could have carried on for a while longer. For the average patient that would frequent clinics to perform this test, achieving maximal exertion may not be something that can be coaxed out of them, especially if they had already endured other tests in the same day.

Already I was beginning to understand the plight of the patient, when it comes to tests that require their full participation, and I still had the hardest one to come… I was not looking forward to the post-lunchbreak activities.

It turns out, the Ramp Protocol test was actually the most enjoyable of the day. Perhaps this was simply because I was growing used to being fatigued/dehydrated, or perhaps it was the setup of the test itself, but I could have happily continued running on the treadmill for a great deal longer than I did, time allowing.

The ramp protocol treadmill test involves the face mask setup presented in the pictures, and a steady speed and incline increase on the treadmill for as long as it takes for the patient to reach their VO2 max, but it is up to the patient when they stop. Unlike the bleep test, which involved travelling at an uncomfortably slow rate at times, the ramp protocol was a fairly rapid journey to a pace similar to that of a distance runner. It was far from comfortable, so would still require a great deal of coaxing and encouragement in order to get the patient to work hard to complete the test, but it was certainly more comfortable than the test that had preceded it.

The whole day not only reminded me of tests and theory that I had almost forgotten, but it really helped me to understand what a patient has to go through when they visit a hospital. The feelings and tests that I personally experienced were, on the whole, not pleasant, but I wanted to be there. For a patient, this will most likely not be the case. When your clinic list is seemingly never-ending and you don’t have time for restarts, it’s easy for the fact that patients don’t know the requirements and procedures as well as you might, to slip your mind, but thanks to this experience, it’s something that I’ll never forget, and I feel it solidifies a vital skill that students require to be able to operate efficiently and fairly: empathy.

Tomorrow brings a different kind of discomfort, in that I will be having my first echocardiogram. I’ll add that experience to part II

The ramp protocol will also get the full write up treatment, as it was by far the most complex and in addition, I have a detailed set of results.

Thanks for reading.

Christopher.