TSP ECG #3

Male, 54 y/o

Comment on rate, rhythm, axis and anything abnormal you can find.

This quiz is a learning tool and is designed to promote discussion, so if you disagree with our analysis, sound off in the comments below; we’re learning, too!

TSP ECG #3

Male, 54 y/o

Comment on rate, rhythm, axis and anything abnormal you can find.

This quiz is a learning tool and is designed to promote discussion, so if you disagree with our analysis, sound off in the comments below; we’re learning, too!

During the festive season, its easy to indulge in excess; too many sprouts, an increase in afternoon napping, festive drinks… You know the score. It isn’t all smiles and sunshine, though, as we shall see.

One particular result of all the festive excess relevant to cardiac professionals, has been reported across the globe, but particularly in Entirely Fictitious Primary Care Centres (EFPCCs); Bacardi Branch Blocks, or BacBBs

BacBBs are thought to affect the heart as a whole, but it can be seen that they have a particularly odd effect on the ventricles, and cause an odd, never-seen-in-real-life depolarisation wave on the ECG, that actually defies physics and medical science by going back in time!

Symptom sheets compared with the compiled ambulatory data have shown unanimously that BacBBs are present sporadically within sinus rhythms, but coincide with that one-drink-too-many during a family game of Monopoly (Mr Moneybags isn’t thought to be an underlying cause, so the activity isn’t seen as a risk factor).

Atrial activity stops altogether, presumably because the SA node just forgets what it’s doing, as it’s seen enough crepe paper hats and screwdriver sets fly from crackers to last it a lifetime.

After an episode of BacBB, sinus rhythm resumes, and the patient will return to whatever their festive-norm may be until the next instance.

This phenomenon seems to disappear entirely during the first couple of weeks of January, when normal working hours begin again, hence, I feel that it is triggered by the holidays themselves.

None of this is being researched, or is even disputed, because it is both totally false, and invented entirely by me.

Bacardi Branch Block

I never considered just how difficult trace analysis could be. Don’t get me wrong; I knew it would be hard, I just didn’t fully appreciate quite how hard.

During lectures on specific arrhythmias, when ECGs are displayed, they generally contain the abnormalities that make up the subject matter so it doesn’t take long to come to the correct answer, but looking at a trace without any history or prompting as to the condition, is still overwhelming to me. So overwhelming, in fact, that I often feel like I’m falling short of the mark with regards to my learning as a whole. The TSP ECG section is as much for my benefit as it is for you guys, in that I’ve found analysing the ones selected for posting incredibly difficult.

No matter what answer I come to, there’s always the lingering worry that I’ve missed something.

How much is too much, with regards to analysing?

What’s a result of over-analyzing, and what’s accurate?

Textbook traces, whether clinical, or stylised, have been selected as the best possible example of the rhythms under scrutiny, so it stands to reason that they won’t exactly mimic those that will be encounered in the field. In my limited experience, clinical traces contain a great deal of variation and have thus far, rarely resembled anything you’d find in a book.

They have been difficult, yes, but they have also been possible. This will all become easier, with practice (I assume/hope), so I hope you all find the analysis quiz good practice, as it’s certainly proving to be that for me.

TSP ECG #1

Male, 80 y/o.

Comment on the rate, rhythm, axis and anything abnormal you can find.

This quiz is a learning tool and is designed to promote discussion, so if you disagree with our analysis, sound off in the comments below; we’re learning, too!

My last article looked at the assessment of Left Ventricular Hypertrophy; its contextual clinical significance and subsequent electrocardiographic findings, and concluded with possible pathological reasons for the development of LVH of which I wanted to discuss in my next article.

Sadly, due to an onslaught of assignments more intimidating than Xerxes Persian army in the film 300, I haven’t had the time to write any subsequent material.

However, now the assignments are over I have the time to explore these pathological causes of LVH.

Just as a recap, LVH is an increase in the size and proportion of the left ventricular myocardium. Just like any muscle, the more it is permitted to carry out work (contract) the greater it will increase in size (hypertrophy).

This increase in muscular size results from increased recruitment of sarcomeres (basic subunit of muscle cells) as well as extra cellular matrix remodeling (the scaffolding material of tissue). As a result of these anatomical adaptations the ventricle changes in size and proportion. Its normal conoid shape may be altered.

Concentric/Eccentric Hypertrophy

This remodeling will present as either Concentric or Eccentric hypertrophy depending on the underlying cause.

Concentric hypertrophy results from chronic pressure overload commonly associated with chronic hypertension and aortic stenosis. New sarcomeres are added in parallel to existing sarcomeres. Wall thickness greatly increases and persistence over time will significantly reduce chamber radius. The remodeled ventricle has reduced contractility and compliance leading to diastolic and eventually systolic dysfunction (impaired filling/ejection).

Eccentric hypertrophy often occurs with volume and pressure overload; pathological associations include heart failure; aortic/mitral regurgitation (volume overload) and chronic hypertension (pressure overload). Ventricular remodeling results in increased chamber radius and moderate increases in wall thickness. Chamber dilation occurs as new sarcomeres are added in series to existing sarcomeres.

Physiological consequences of LVH

LVH usually develops as a compensatory response to the underlying pathologies mentioned above. Increased arterial pressure (afterload) as a result of chronic hypertension and/or aortic stenosis increases the pressure required of the LV to eject this blood. Increased LV wall tension compensates via concentric hypertrophy.

Volume overload within the heart (heart failure) is often a resultant of valvular regurgitation and/or systolic dysfunction. Aortic/mitral regurgitation will increase the volume of blood left in the ventricle after systole (End Systolic Volume). During the next systolic cycle the LV has to contract with greater force to eject this increased volume of blood (End Diastolic Volume). Frank Starlings law of the heart states that increased stretch on the myocardial wall (Preload) increases strength of contraction. This pressure/volume overload induces chamber dilation and eccentric hypertrophy.

The hypertrophied LV becomes less compliant reducing its filling and contractile capacities. This culminates in systolic dysfunction. Systolic dysfunction is a significant reduction in cardiac output and will present with symptoms of dizziness, fatigue and shortness of breath. Systolic dysfunction of the LV will also lead to pulmonary congestion due to the back up of pressure generated by increased atrial and pulmonary venous pressures resulting from the increased EDV.

LVH is one of the strongest predictors of cardiac morbidity in hypertensive patients. The degree of hypertrophy correlates with the development of congestive heart failure, angina, arrhythmia, myocardial infarction and cardiac death (Lilly).

Another pathological subcategory I have not eluded to that is also a major contributor to LVH is cardiomyopathies. This is something I will look at in detail in my next article. Thanks for reading 🙂

I’d just like to take the opportunity to thank my good friend and partner in crime Christopher Wild for firstly creating this fantastic physiology based resource and secondly giving me the opportunity to participate in its progression.

3 months since creation and the TSP has already received nearly 1500 hits, recognition and support from numerous universities and academics across the country as well as our professional governing body.

My buddy deserves massive acclamation for this achievement and I know there is much more to come!

Whilst writing this article it has again reminded me how interconnected many pathologies, symptoms and clinical findings can be. About half way through writing I felt as though I’d opened a big can of worms as there are so many different tangents on which you could proceed to discuss. Added to this is the limited knowledge I have as I’m only a second year student! Therefore please don’t take this information as cardiology gospel! I have and always will, use reliable sources of information, but this is my interpretation of such material and I can’t guarantee inclusion of every detail. Nevertheless, I have personally found writing such articles to be of great benefit; and thus if there are any other physiology students out there that may be interested in writing for TSP we would greatly welcome your support.

Ref:

http://www.cvphysiology.com/Heart%20Failure/HF009.htm

Image from:

If you visit this site regularly, or follow the TSP twitter, you’ll hopefully be aware that I try to post updates and tweet fairly regularly. Sometimes they are in the form of personal pieces such as this, sometimes they are reviews or study guides, sometimes minor news updates or small tweaks to the site itself.

If you’ve visited this site recently, however, you might have noticed that I haven’t updated it for a little while. There’s one reason for this, and one reason alone: the assignment.

I’m seeing the light at the end of the tunnel as I type this, due to the fact that my extended case study is now submitted. It was a great piece of work to take on, too. Three sections in total, each with its own word count. The first was a patient case study, with a provided patient history, two electrocardiography traces to analyse and compare, and the subsequent report and treatment pathway to complete. This was probably the most fun of the three, but also the most time consuming.

The second was a broad topic that had to be condensed into a relatively small word count. This was, without question, the most difficult of the three sections and whilst I’m confident in the content I submitted, it’ll be interesting to read my feedback and see how well I interpreted the question.

The third, a brief similar to the second section only with a much more specific topic was initially fairly free-flowing, in terms of writing, but the further I progressed through it, the further away that word count looked. What began as a torrent of information on the page, soon trickled to a halt, as I realised I had explored all of the avenues in my plan without leaving room for branching out. As a result, I had to go back through every paragraph and find some wiggle room to potentially add another facet to the discussion.

I’m being intentionally vague so as not to disclose any details of the assignment, rather I’m confirming what we all know about assignments; there are some we like, and there are some that we loathe.

If you’re currently in the midst of a large piece of work, don’t panic! Just power through. Don’t worry about your friends posting Facebook updates from the pub, don’t worry about your Christmas shopping just yet. I know it’s easier said than done, of course, but despite the fact that (technology permitting) this article has gone live at around 3pm, as I type this, it’s 4.30am. Pressing that ‘submit’ button on my coursework has sent me into a state of fatigued euphoria, and all the late nights have been worth it.

I’ll add that on top of this assignment, I also have deadlines for an Inter-professional Collaboration self-reflective essay and a presentation on cardiac technology in the same week. Next week.

Until then, it’ll be a bit quieter around here…

Download the android app: Free

Purchase the monitor: £75 approx.

Developer: AliveCor, David Albert

Thus far, my reviews have been mostly confined to apps, with the only exception being Windows/Linux software, simECG. This review is quite exciting for me, as it involves a physical monitor as well as a companion app. I picked up the now world-famous AliveCor Mobile ECG Monitor a couple of days ago to road test it, and I’m pleased to say that for patients, it’s fantastic, and for students, it’s just as good.

As far as functionality goes, this app serves as a personal event monitor with a particular focus on atrial fibrillation, and it has a ton of nice features that make it a worthwhile investment for patients regular to cardiac departments.

Out of the box, the dual-electrode plate can be attached to the back of your mobile device via an adhesive strip, or kept separate; AliveCor works either way, and if you do attach the monitor and change your phone, you can pick up additional attachment plates for around £6.

Obtaining a trace is a very quick process; it only took me a few seconds to open the app and begin recording, and the trace is saved automatically after 15 seconds, with the limit set at 30. The user is then presented with a series of tick-able boxes such as hand or chest ECG, and a notes section to document any symptoms. These are then stored with the trace.

In this video, you can see that AliveCor jumps straight into recording once fired up.

Heart rate and beat fluctuation are tracked and graphed automatically to allow patients to relate multiple recordings in conjunction with the particular activity being performed during monitor operation.

In addition to this, the app comes with an algorithm that determines the presence of atrial fibrillation and keeps track of how many instances this occurs.

AliveCor offers a great deal of options when it comes to sharing data and to physical useage: once the trace has been recorded, the user can email it, save it as a fully notated PDF and print either from the app or a different program.

Holding the device in your hands, as shown in the app instructions gives you a trace in lead I, and it’s possible to obtain leads II and III by placing the two electrodes in different areas of the body (I have provided these instructions at the bottom of the page). Handily, AliveCor doesn’t just measure biopotentials in the peripherals, but also in the chest. A Lewis lead configuration is possible to view atrial activity with more clarity.

I experienced a minor issue with artefact at the start of recording, but this was almost definitely user error, as AliveCor ‘steadies’ itself pretty quickly if you remain relaxed and support you arms. This learning curve is honestly the only problem I had with the product, and after 10 or so minutes, it wasn’t a problem at all. I don’t want to speak for everyone, but I feel it’s fairly easy to get to grips with, so I doubt that your average patient would have too much trouble with it after a short while.

Traces themselves look very clean and, thanks to the standard calibration and the inclusion of a regular ECG paper grid, various amplitudes, intervals and waveforms can be measured manually. The trace screen also gives the option to invert the recording, and filter enhancement is selectable for each one.

As an event monitor, this device is invaluable. It comes with its own built-in symptom sheet and it’s incredibly quick and easy to record a good quality trace. AliveCor has been given the thumbs up from the FDA and NICE, so it’ll be interesting to see how the SCST view the monitor; I’ve reached out to them, but haven’t heard anything yet. If I do, I shall update accordingly.

I assume that in the U.S. this app allows patients to forgo some of the high cost of continued medical care by way of allowing the trace to be sent directly to a clinician for review. The UK version gives the option to send the trace to a Cardiac Physiologist for £5 and provides the analysis results within 24 hours, allowing the patient to present an official ECG report to their GP, should they need to.

As an added bonus, the AliveCor app has an educational area that features breakdowns of common arrhythmias and cardiac anatomy. The illustrations are aesthetically very pleasing and straightforward. The information contained within it is not as comprehensive as the information you’ll find in your lectures or textbooks, but it isn’t designed for the use of practitioners, so what is there is entirely sufficient.

All in all, AliveCor truly is a technical feat and not only does exactly what it sets out to do, but gives a glimpse of the future of ECG technology. This is an extremely good way for patients to become actively involved in their own heart health, with a relatively small price tag. The app provides a simple, intuitive UI and doesn’t require any Bluetooth connectivity between monitor and phone: it works right out of the box so that any patient can use it with ease. There’s a reason this product has garnered praise around the globe.

I will add that the device’s creator, Dr David Albert, is one of the nicest individuals with whom I have ever had the pleasure of conversing. His instructions for getting the most out of AliveCor for the purposes of this review have been invaluable, and even though he really didn’t have to, he answered every question I asked him, swiftly too. I’d like to thank David for being kind enough to help me get to grips with the product all the way from his residence in Oklahoma. Students need input such as this; it cements that we are valued and encourages learning outside of regular studies.

Positioning data:

Lead I: LH – RH

Lead II: LL (knee) – RH

Lead III: LL – LH

Lewis: Electrode 1 on V1, device angled vertically

Download for Windows/Linux: Free

Developers: Antonio Cardoso Martins, Paulo Dias Costa, Joao Miguel Marques

I’ve been searching for a half-decent ECG simulator since last year, but hadn’t found one that costs less than “more than I have”, so I was pleasantly surprised to find the rather unnecessarily named simECG: ECG Simulator for free, on Windows and Linux.

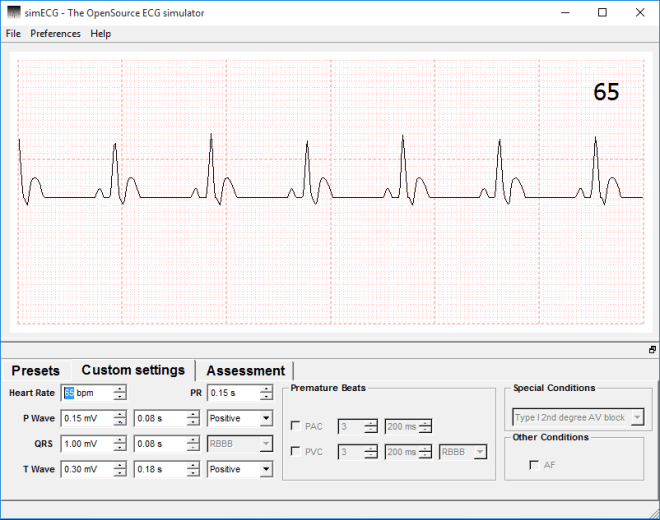

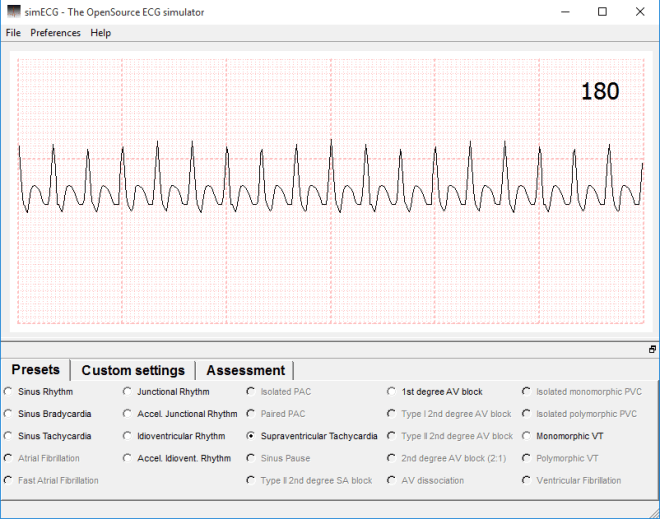

simECG offers a number of functions in its current version. The operator can select from a series of common arrhythmias at the click of a button, and observe the associated waveform on the display. Unfortunately, only a handful of options are actually selectable, at present, with the others showing as greyed out, presumably, as with many Open Source programs, until they are finalised by the development team.

The custom settings tab provides the means to alter each area of the trace individually, adjusting heart rate, P wave amplitude/duration and more, and watching the displayed trace change in real time. The program hints at future save/load functions for your altered settings, too, which will be a nice inclusion for educators to make use of.

All of the aforementioned are easy to use and clearly marked, even if there aren’t currently all that many of them.

The option exists to change the background between ECG paper and a monitor screen, although the ECG paper skin is purely cosmetic. It would have been nice if the paper option was more in correlation with the amplitudes and durations selectable in the readout options. Greyed out sections of the “preferences” tab hint that calibration will soon be able to be changed by the user, so it would be preferable for beginners and students if these proposed calibration options had a realistic background to use in conjunction with the created trace.

I couldn’t find an option to reset the trace at all, even in a greyed out form, and as a result, returning to the default custom settings is something of a chore. Hopefully this is something the developers will consider including in future iterations.

By now you may have noticed the appearance of the waveforms in the above trace. The trace waveform was one of the first things I noticed, as the whole thing doesn’t look right. The P and T waves look malformed, with the latter presenting almost as though the patient was displaying hyperkalaemia despite this being labeled as a normal sinus ECG.

The assessment quiz tab gives the user an opportunity to identify 10 rhythms in 60 seconds. It’s fun, sure, but given the odd appearance of the waveforms, it becomes a case of memorising the traces present in this program alone, as they aren’t all applicable to real life.

I’ll be honest, it’s hard to criticise something that the developers admit will “never be finished” due to its Open Source status, but the nature of this website and Open Source in general means it pays to remain objective. In actuality, whilst I have highlighted a few issues, the fact that this tool is ever-evolving and totally free, means I can only commend the development team for their ethos and hard work.

Martins, Costa and Marquez state their belief that education shouldn’t be a corporate tool, or purchasable commodity, rather it should be accessible to all. The more people there are to flag issues, the better an idea the team can have of what functionality to add, what bugs to fix, and what other changes are felt to be necessary by users. Despite being generally incomplete at present, it’s not only one to watch for in the future, but one I’d ask every cardiac physiologist to download and play around with.

Due to this version still being in the 1.n phase, I have high hopes for the future of this software, as it has great potential as a learning tool. With the addition of more options in the preset tab, further wave/interval customisation, and more accurate waveforms in general, simECG could help physiology students consolidate their knowledge without carting loads of textbooks around, making it an essential bit of kit.

Yesterday, on the 20th of November, Oli and I attended the SCST annual update meeting. It’s the first physiology conference I’ve attended that wasn’t tied to one specific trust (the last one I attended was the Royal United Hospital’s respiratory medicine conference), rather, it was applicable to and attended by cardiac scientists from across the four home nations. The day was packed with talks, networking opportunities and insight into the future of the science. Speakers hailed from a variety of professions and organisations, but all were entrenched in the science of cardiology and education.

Due to the long distance travel and Birmingham’s seemingly city-wide roadworks, Oli and I missed the introduction, but we were present for the rest of the day and we recorded and annotated everything else, so whilst I’ll provide an overview here, detailed breakdowns of everything relevant to PTP study will be supplied separately, as and when time and my coursework volume allows.

Of particular note is the information on preceptorship qualification, delivered by Sophie Blackman of SCST and Boston Scientific. I collared her after the event proper, and she kindly agreed to provide the literature pertaining to this, so as soon as it’s available, I’ll add it for you all to have a mosey over. It seems like a great opportunity for newly- qualified practitioners to become super confident in all aspects of their job, so I highly recommend that you read the contents when they’re available.

Dr Patricia Oakley of King’s College outlined the plans for a new variety of health clinic: the centre that isn’t home and isn’t a hospital, but the “place in the middle”. These will be networked, multidisciplinary centres, featuring social workers, scientists, psychiatrists, GP’s, etc, so cardiac physiologists will most likely be a necessity in their implementation. The whole session really drove home the emerging importance of this profession, but also the requirement of all of us, student and qualified, to ensure that the cardiac physiologist is recognised as being at the forefront of innovation so as not to be overlooked. It was mentioned more than once, that if we don’t put ourselves forward for emerging structures, someone else will.

Dr Oakley told of the need to reduce treatment variability by region. Her example was the treatment of amputation as a result of diabetes; Devon has, by far, the highest number of below-hip amputations when compared with the rest of the UK, due to the fact that the majority of Devonian surgeons trained under a surgeon who has a penchant for this level of removal. The advent of these networked clinics will reduce this level of variability and promote consistency across the home nations.

The president of the AHCS, Dr Brendan Cooper delivered the final talk of the day, discussing the future role of the healthcare scientist in wider healthcare and medicine, and the need for physiologist prescribing. I’ll provide a detailed breakdown of this talk next, and shall hopefully post it in this coming week.

The fact that this specialist degree exists primarily in universities is a relatively new event; before the shakeup by Modernising Scientific Careers, the majority of training was completed in-house with an element of distance learning thrown in to assist with the theory behind the practical concepts.

As physiological science makes the transition to a 100% university- led discipline, there remain students that are still learning the “old way”. Sarah is one of those people, and I had the pleasure of working with her this year during my rotations between respiratory medicine and cardiology. In order to get a bit of insight into exactly how the course differs between bases, she kindly agreed to be interviewed for TSP.

Hello Sarah! Could you outline the structure of your week, with regards to working in your department and studying the degree simultaneously?

I’m employed by the hospital, so have to work my set hours which are Monday – Friday 08.30-16.30. Although I’m studying, I am not employed as a student, rather, I am an Assistant Technical Officer, which basically means I help around the department doing admin, portering and some clinical work. I have certain responsibilities with regards to admin that I have to keep on top of regardless of what clinical work I need to be learning.

Monday is my main admin day, so I spend the entire day sorting through referrals, checking messages & booking appointments for certain procedures that only I book. I need to keep on top of this as some of the procedures have extremely long waiting lists, so if a patient cancels last minute I need to try my best to fill that slot. Once my admin is complete I normally help out my colleague in the office with some of her work load. If there is no porter to bring inpatients up & back for echocardiograms then it is part of my job to do this as well, which means I can’t get my necessary admin work completed.

Tuesday is the start of my clinical week, unless I have been portering the previous day. At the moment I am spending all day Tuesday in analysis, analysing 24 hour and 48 hour tapes. I am able to analyse a tape independently, but as I am still learning they all need to be checked after, just in case I’ve missed something or worded my report incorrectly.

Wednesday is a half day in the department for me as I have a collaborate session starting at 12.00 so I need to be set up in the library ready to start. After my collaborate session I catch up on any studying I need to do, such as looking over lectures that have been released for the following week, researching/ writing an assignment or revising for upcoming exams. On a Wednesday morning I will either be fitting ambulatory blood pressure monitors (supervised, as I am not confident to do them alone yet) or analysing.

Thursday mornings I am in Electrocardiography, either in the department or going down to the ward, and in the afternoon I analyse.

Friday mornings I do tape clinic which occupies the entire morning and keeps me very busy, especially if I have patients returning that have had symptoms of dizziness & I need to get the tapes checked before I can let them go. I spend Friday afternoons in analysis.

That is my current working week, but I will start going on the rota soon to sit in on exercise treadmill tests as well. Most mornings I get into work at around 07.30 so I can get some studying done before work and I try to do an hour or so in the evening as well. Most weekends I keep to myself, but if I have an assignment due or exams I will do a couple of hours each day.

That’s a hectic week. This might now be a silly question, but do you feel that this is this enough?

In terms of clinical exposure … yes! But it is very hard to keep up with the academic work load when there is very little time to fit things in. I commute for over 2 hours a day so this eats into my potential study time, but I try to keep a balance of work, study and actually having a life!

Do you feel that working in the same department as you study helps you to learn more and keep you motivated?

I feel that second year especially has helped me learn, but most of the academic work in our first year wasn’t particularly relevant to cardiology. I feel like I learnt more in the last 2 months from analysing tapes than I have in the whole 2 years that I’ve worked in the department. I definitely think it has helped to keep me motivated as I’m constantly surrounded by people that are doing the job I am training for, so I’ve got a clear goal at the end of it.

You’re one of the last sets of the distance intake. Do you think, if you had the choice, you’d still do the degree in the manner you currently are, or would you choose to be based at the university?

I’ve already done a previous degree so I’ve experienced the whole student life thing, so I’m not missing out by doing it this way. At the moment I am essentially being paid to learn, which is ideal. I wouldn’t be able to afford to do this degree if I was based at the university, as I’ve already had a student loan so I’m not entitled to another. I think I get a good amount of exposure in the clinical setting, but I just have to do some of the boring admin jobs to make up for it. At the end of my degree I will have a job and I know 100% that this is the career I want for myself. I wasn’t passionate about my previous degree subject so I lost interest and didn’t want to spend the rest of my life doing it, whereas I know from working in this department and from studying the way I am, that this is what I want to do. I don’t think I’d have that level of clarity if I was based more at the university than the hospital.

That’s fair. When we worked together during my placement, I was aware of the fact that you were much more comfortable in the clinic environment than I was (obviously), so what do you feel we at the university have by way of an advantage?

I definitely think that as I’m exposed to patients and the environment all day every day that I am more confident and comfortable than yourself, but I would say that full time students based at the university have a lot more academic knowledge. We have 1/2 hours a week of contact time with our lecturers so we need to go out and research ourselves, whereas it is clear that you guys have a lot more academic time although you miss out a lot with the lack of placement.

Thanks, Sarah!

As you can probably tell, despite the fact that Sarah and myself are in the same cohort, our academic years have a vastly different focus. As I (rightly) assumed just from working with her on the department, both routes present their pros and cons, and seeing as this is a vastly understaffed form of diagnostic science, it does, in my opinion, open the career up to a greater number of people now it will be university- led.

If you’ve got an opinion, or a question regarding anything you’ve read, sound off in the comments below.

Photo courtesy of Facebook